Lancaster County cuisine is a humble cuisine. For centuries, our Amish and Mennonite kitchen gardens have produced farmers’ food—basic, unassuming meals that are meant to “stick to your ribs” and nourish your soul. My Mennonite grandmothers were not trend-setting gourmets. They knew nothing of nouvelle brunches, or spa cuisine, or macrobiotic dinners. Our food, here, is not about tarragon sauce and angel-hair pasta. We think in terms of quantity, not subtlety, at our farm tables.

For many visiting food lovers, it comes as a great surprise, then, to discover that our rural Pennsylvania Dutch cooks are connoisseurs of the world’s most expensive and exotic spice—saffron. Elsewhere, this garden spice is often shrouded in an aura of exotic mystery, but Lancaster County gardeners have been growing it alongside the cabbages for centuries.

Related article: Related article:

• Saffron in the Pennsylvania Dutch Tradition |

|

Saffron usually means classical European cuisine, not American farm food. It is meant for risotto in Milan, and bouillabaisse in Marseilles, and paella in Madrid. But thankfully, it is also meant for chicken pot pie in Lancaster County.

Here, saffron is not the extravagant luxury it is thought to be elsewhere. Roman emperors bathed in saffron-scented waters and carpeted their theaters with the purple blossoms. Mennonites never did all that. Saffron, for us, means food—chicken dishes. This crocus provides the deep yellow color and pungent flavor that is critical for the success of some of our most traditional dishes. Actually, any dish using poultry or egg noodles is fair game for saffron in Lancaster County. Our traditional cuisine calls for this yellow seasoning so frequently that we have been referred to as the “Yellow Dutch.”

[[[PAGE]]]

The dollars and sense of saffron

My grandparents and theirs before them would have been surprised to hear you refer to their unpretentious garden plant as the world’s most expensive spice. When saffron has been growing beside your wood shed for generations, it seems as cheap as dirt.

| Sources for saffron bulbs:

McClure & Zimmerman Wayside Gardens |

|

It has always made good sense to grow your own saffron. If you have to buy it, this spice truly is as expensive as its reputation suggests. Producing saffron commercially is hugely labor intensive. It takes 75,000 blossoms to produce just a pound of dried saffron threads that wholesale for $70 per ounce.

The saffron crocus, Crocus sativus, is an excellent addition to any landscape in Zone 6 through Zone 9. It pays for its garden space many times over with its burst of autumn color and its grasslike foliage that stays green all winter.

|

|

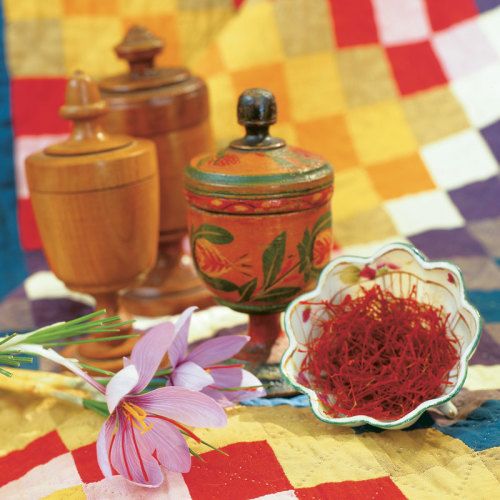

| At the center of the purple flowers of the saffron crocus are three red stigmas, which are harvested and dried to produce a valued spice. |

Saffron is a crocus with personality. It defies the traditional gardening season by lying dormant all summer, and then, when the rest of the garden is turning black with frost, it pushes its purple blossoms up through the mulch to announce its dramatic presence. Each blossom offers up to three scarlet stigmas, the female reproductive organs, to be picked for the next stew or salad or dessert.

Saffron can be a slowly acquired taste. The flavor is unlike any other, and has been variously described as “pleasantly bitter,” “earthy,” and “briny.” Of course, if you are Yellow Dutch, it tastes exactly as you want it to.

The color that saffron contributes to egg noodle meals can be equally surprising to saffron novices. The ideal is a warm, buttery glow. A cook’s heavy hand, though, can produce a dish that seems more crayon yellow than buttery. But here in Lancaster County, we don’t mind that unusual yellow at all.

[[[PAGE]]]

Growing your own couldn’t be easier

Despite saffron’s exotic reputation, it is child’s play to grow. This species is neither finicky nor temperamental, it is disease and insect resistant, and it requires little attention year after year. Its requirements are simple: Plant the bulbs (technically they’re corms) in the summer, harvest the stigmas in the fall, and if you get around to it, divide the plants every four years or so.

|

|

| A saffron bed that’s ready for harvest. | |

|

|

| To dry harvested saffron threads, place the strands on a paper towel for several days in a warm, dry place. |

Growing saffron does require patience, even if it doesn’t require skill. A standard “starter kit” of 50 saffron bulbs will cost around $40 or $50, and will produce less than a tablespoon of seasoning the first harvest. Each year, though, you get more blossoms and more spice from these bulbs, increasing from one or two blooms per bulb the first year, to eight blooms or more by the third year.

Plant the corms 6 in. apart and 3 in. deep in rich, well-drained soil. Using your 50 bulbs, this will create a saffron bed about 2 ft. by 5 ft. As a bonus, you may plant this bed with summer annuals, while the saffron is lying in wait beneath the mulch for its autumn growing season. My great grandmother, Barbara Stoner, always grew portulaca in her saffron bed, and that combination is excellent for any century. When cold weather begins to nip at the portulaca, you pull it out, and there is the saffron, pushing up for its turn in the October sunshine.

Fresh saffron threads can be used immediately for cooking, or they can be dried and stored. Here in Lancaster County, a folk art form has evolved for the sole purpose of storing saffron. We have created our own saffron boxes—miniature containers, shaped like egg cups, for storing this valuable spice. When these prized antiques show up at auction, they sell for more than their weight in gold.

Drying the saffron threads is a simple process of placing the strands on a paper towel for several days in a warm, dry place. You should then transfer the dried saffron to an airtight container and keep it in on a cool shelf, ready for your next yellow chicken dish.

| Containers fit for the king of spices Lancaster County is a hot spot of American folk art. Pennsylvania German arts and antiques command international attention from museums and connoisseurs who appreciate the timeless quality of our regional craftsmanship. Our county’s signature spice, saffron, plays a curious role in this folk art tradition. Rural Lancaster County was so fond of this yellow seasoning that around the turn of the century, several Mennonite farmers began crafting saffron boxes—folksy, hand-made containers that resemble goblets with lids.

Today, Lehnware can no longer be called humble. When a good Lehn seed chest surfaces, no one blinks when the gavel drops at $48,000. Fortunately for saffron fans, Lehn saffron boxes are more affordable. But then folk art is not about money, it is about heritage. And if it is Lehnware, it is even about food. |

by Clarke Hess

December 1997

from issue #12

One farmer in particular, Joseph Lehn, became the master of the saffron box. Lehn was a self-proclaimed preacher and part-time barrel maker who turned to woodworking in the mid 1800s to supplement his income. He became a whiz on the treadle lathe, which he used to turn out egg cups, salt cellars, and most importantly, saffron boxes. Then, like the best Pennsylvania craftsmen, Lehn turned utilitarian objects into folk art by decorating these humble pieces with his homemade paints. His best saffron boxes are smothered in garlands of strawberries, pussy willow, and pomegranates.

One farmer in particular, Joseph Lehn, became the master of the saffron box. Lehn was a self-proclaimed preacher and part-time barrel maker who turned to woodworking in the mid 1800s to supplement his income. He became a whiz on the treadle lathe, which he used to turn out egg cups, salt cellars, and most importantly, saffron boxes. Then, like the best Pennsylvania craftsmen, Lehn turned utilitarian objects into folk art by decorating these humble pieces with his homemade paints. His best saffron boxes are smothered in garlands of strawberries, pussy willow, and pomegranates.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in